The Second Draft - Volume 37, No. 2

The Tortured Lawyers Department: What Taylor Swift’s Newest Album Can Teach Students About Persuasive Legal Writing DOWNLOAD PDF

October 31, 2024-

Introduction

On April 19, 2024, Taylor Swift dropped her newest album, The Tortured Poets Department (and The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology).[1] The lyrical savant takes listeners through a journey of happiness, heartbreak, affairs, post-mortem examinations, alien abductions, zombies, Super Bowls, and, of course, Florida. Although law students everywhere likely listened to the album while studying for (or to escape from) finals, those with a keen ear might have picked up a few writing tips to assist them with their final assignments. Indeed, if students began to look outside of the law-library walls, they would find a plethora of nonlegal materials that could aid their writing. In that vein, this piece seeks to (1) encourage legal-writing professors to use nonlegal, pop-culture content to introduce legal-writing concepts in the classroom, (2) provide an example of such practice by using the The Tortured Poets Department’s lyrics to cover persuasive-writing techniques, and (3) honor the queen of contemporary music.

To teach persuasive legal writing, professors often lead students in examining example appellate briefs and other legal material with the hope that students hone in on nuanced persuasive techniques, such as the rhetoric triangle, theme, and word choice. There is an inherent difficulty in this task, however, as students may find both the materials and the persuasive-writing concepts foreign. But in reality, students are familiar with most persuasive-writing concepts, just outside of the legal context. Students are flooded by advertisements on a daily basis trying to persuade them to buy particular products. Podcasters have overtaken our favorite music streaming services trying to persuade students to the podcasters’ viewpoints. Documentaries remain pervasive on Netflix, but instead of neutrally proffering facts, the storytellers often try to persuade viewers through a biased lens of the story.[2] All of these mediums use the concepts we employ in persuasive legal writing. Students may not have names for the concepts, but they are certainly familiar with them. I propose that if we use these familiar mediums to introduce and solidify persuasive-writing concepts, students will be more confident and better equipped moving into legal writing, and ultimately more successful.[3]

To provide an example, let’s take The Tortured Poets Department to teach a handful of persuasive-writing techniques.

- Rhetoric Triangle. To begin, let’s take the rhetoric triangle, which consists of logos, ethos, and pathos. In some ways, these three concepts present the building blocks of persuasive argument.[4] Logos “is rational argument through logical reasoning,” ethos “is the speaker’s or writer’s effort to establish credibility in the eyes of the reader or audience,” and pathos “is an effort to influence the reader’s or the audience’s emotions in favor of the advocate’s position.”[5] In the most basic writing, these concepts present themselves as independent points within an argument. In the most advanced, they are woven together, overlapping throughout the writing.

Swift beautifully illustrates how these three rhetoric functions can coexist in thanK you aIMee.[6] The song features two characters, Swift and “aIMee,” and their tumultuous history. Swift makes the case for herself by simply laying out what “aIMee” did to her, i.e., logos: “And it wasn’t a fair fight / Or a clean Kill / Each time that aIMee stomped across my grave / And then she wrote headlines / In the local paper laughing at each baby step I’d take.”[7] Swift brilliantly builds her own credibility by juxtaposing those actions with her reactions, i.e., ethos: “All that time you were throwin’ punches / I was buildin’ something”[8]; “I wrote a thousand songs that you find uncool / I built a legacy that you can’t undo / But when I count the scars / There’s a moment of truth / That there wouldn’t be this / If there hadn’t been you.”[9] In doing this, Swift argues that she took the proverbial high road. And if this weren’t enough, Swift uses powerful language to draw on listeners’ emotions, i.e., pathos. Again, Swift talks about how “aIMee stomped across [her] grave”[10] and how the “blood was gushin’”[11] as she cursed her antagonist.

In less than five minutes, Swift packs in more of the rhetoric triangle than most lawyers do in thirty pages. But by focusing on each function in turn, students can rival even Swift’s persuasive genius. In legal writing, I encourage students to begin with logos and simply draft a clear, logical argument. Then, I suggest students take up the task of pathos by incorporating a theme or narrative into their argument that resonates with the reader on an emotional level. Finally, students should determine whether there is any space to develop ethos. First and foremost, ethos is built through the writing itself, presenting the reader with a well-drafted, thought-out piece.[12] After becoming comfortable with this basic process, students can begin incorporating the rhetorical devices discussed below to elevate their writing. Some devices may include all of the rhetorical functions. For example, a metaphor can single-handedly clarify a substantive point through analogy (logos), elevate the writer’s credibility (ethos), and invoke emotional reactions (pathos).[13] With a little practice, students can rival Swift’s mastery of the rhetoric triangle.

- Basic Rhetorical Devices. As just shown, basic literary, or rhetorical, devices like metaphors can breathe life into otherwise mundane and complex legal arguments, captivating the tired eyes of a well-read judge.[14] Not only do these devices entertain, but they connect the reader to the writer (or, rather, the writer’s client) through shared experiences and normative values.[15] The following list briefly surveys some of the techniques Swift employs in her songs, which, if used appropriately, can turn any black-letter-law argument into a colorful and persuasive piece of literature:

a. Metaphors and Similes:

Metaphors and similes help bridge foreign concepts to more familiar ones. As a reminder, a metaphor is “a figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them.”[16] Metaphors are commonplace in the law, providing shorthand references to nuanced concepts.[17] They are also extremely useful in persuasive writing because they can help the writer convey complex, abstract ideas through more simple, tangible ones.[18] Swift knows the power of metaphors all too well. Her lyrics are replete with them; the following are just a few examples:

- “I’m an Aston Martin / That you steered straight into the ditch / Then ran and hid”[19];

- “You hung me on your wall / Stabbed me with your push pins”[20];

- “I’m just a paperweight.”[21]

Swift is also known for using an abundance of similes. Similar to metaphors, similes compare unrelated items using “like” or “as.” While similes may not be as vivid as metaphors, their structure “prompts the reader to become aware of the analogical work being done,” which may enhance the clarity of the writing.[22] Again, here are a few examples from Swift’s lyrics:

- “I scratch your head, you fall asleep / Like a tattooed golden retriever”[23];

- “Crash the party like a record scratch as I scream / ‘Who’s afraid of little old me?’”[24];

- “The smoke cloud billows out his mouth / Like a freight train through a small town”[25];

- “These chemicals hit me like white wine.”[26]

Especially when writing about niche areas of the law or overly technical facts, students should spend time considering how to make their argument more palatable to the reader by tying the concepts to ideas more widely understood. By using metaphors and similes like Swift, students can establish common ground with their readers, present clearer argument, and keep their audience entertained in the process.

b. Irony:

Irony is generally characterized as a “contradiction or incongruity between what is expected and what actually occurs.”[27] However, people are often quick to identify something as ironic that isn’t by definition.[28] Grounding the definition in examples can help students better understand the concept. For example, Swift laments that “My boy only breaks his favorite toys.”[29] The idea that someone only breaks what is most meaningful to them is incongruent with how one would expect such person to treat such things, eliciting an implicit irony.

Irony is not the most common technique in legal writing, but if used correctly, it can be incredibly persuasive to frame the opposing side’s argument as the “incongruent” result of the case. For example, students may employ it “to draw attention to discrepancies between the law and justice, or between a legal entity’s stated principles and actions.”[30] Creating this dissonance in the reader’s analysis of the opposing side’s argument may persuade the reader to your point of view.

c. Foreshadowing:

Foreshadowing is hinting at what’s to come. Swift is well-known for her foreshadowing in the form of “Easter eggs,” small references that hint to her next project. Swift continues this practice in Fortnight, where Post Malone sings, “Move to Florida, buy the car you want.”[31] The reference to “Florida” subtly hints to the subsequent track, “Florida!!!”[32] If done in a similar fashion in legal writing, foreshadowing can be a powerful persuasive tool because it allows the reader to feel like they are in control of the story.[33] Students should strive to write their fact sections in such a way that the reader feels the “natural” outcome of the case favors the client before ever reaching the legal analysis.

- Theme. One of the best ways for students to build pathos (and to some extent, logos) with their audience is through a captivating and universal theme. However, I find that students (and attorneys) seem to have particular difficulty in grasping “theme” and incorporating it into their writing. Students seem to understand how to blend logical arguments together and fold in some emotional rhetoric, but rare are the students who can truly weave their argument into a cohesive story. Most often, students introduce their theme through an introductory sentence but never revisit it in their writing.

Swift provides three examples that express what strong themes look like, though they are a little on-the-nose for legal writing. In My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys, Swift compares one of her previous relationships to children playing with various toys.[34] This theme isn’t limited to a simple hook or the chorus but instead permeates the entire song through effective word choice. For example, Swift repeatedly compares herself to a doll: “Rivulets descend my plastic smile”[35]; “Put me back on my shelf / But first, pull the string”[36]; “Cause he took me out of my box.”[37] Swift further emphasizes her theme through the language she uses to describe their love: “Puzzle pieces in the dead of night”[38]; “Down at the sandlot / I felt more when we played pretend / Than with all the Kens.”[39] What students should take away is that almost every line incorporates her theme by including references to toys. Moreover, this is a theme—someone breaking a favorite toy—with which virtually everyone can relate through past experiences.

Another great example is found in So High School, where Swift similarly compares her (current) relationship to the feeling of being in high school.[40] Again, Swift thoughtfully chooses each lyric to evoke a sense of nostalgia. She further captures a wide breadth of listeners by referencing pop culture that transcends generations: “I’m watching American Pie with you on a Saturday night”[41]; “Are you gonna marry, kiss, or kill me?”[42]; “Truth, dare, spin bottles”[43]; “Touch me while your bros play Grand Theft Auto.”[44] In doing this, she connects her story to her listeners by evoking shared emotions, memories, and stories.

Finally, Down Bad presents an interesting example of theme.[45] In the song, Swift describes a borderline-Stockholm-syndrome relationship through the tale of an alien abduction. She moves back and forth in her lyrics, describing how her paramour experimented on her but then left her “naked and alone.”[46] Despite “waking up in blood,”[47] she is still drawn to her love and this otherworldly experience. I personally enjoy her line: “They’ll say I’m nuts if I talk about the existence of you.”[48] Maintaining the alien-abduction rhetoric, she conveys how no one will believe her nor will they understand the experiences she went through in this relationship. Although “no one” has experienced an alien abduction, we are so familiar with this narrative from pop culture that the theme still resonates with us.

Although students would be wise to exercise more subtlety than Swift, it is worth viewing these hyperbolic examples of theme to better understand how to employ the concept in a legal setting. Whether it is “justice,” “equity,” “rule of law,” or something more granular, students should ask themselves if their theme can be found beyond their introductory sentence and throughout their piece—even in their word choice. If successful, students can connect the foreign subject matter of their writing to more-universal concepts and are more likely to persuade their reader.

- Word Choice. Students who have followed Swift through her eras have likely expanded their vocabulary in more-recent years. But word choice provides more than an opportunity to appear smarter. (To the contrary, see the caution below.) Instead, it enables students to construct their themes and provoke emotions at a granular level (i.e., with each word). Swift never misses an opportunity to choose words that further her theme. For example, in Fresh Out the Slammer, Swift admits she was “handcuffed” to the spell of her lover, perpetuating the theme of a prison.[49] Choosing words carefully also involves taking a bland word and crafting it into a descriptive phrase that leaps off the page.[50] For example, in Fortnight, Swift could have simply referred to “dull mornings,” but instead she provides the universally understood description of “Mondays stuck in an endless February.”[51] Descriptive word choice also transports the reader and places them mentally within your narrative. Take the bridge of The Alchemy. Listeners can almost feel their feet sticking to the beer-soaked floor at a championship-game celebration because Swift uses descriptive language to draw upon multiple senses.[52] In the same manner, students can place readers in the client’s shoes and create significant empathy.

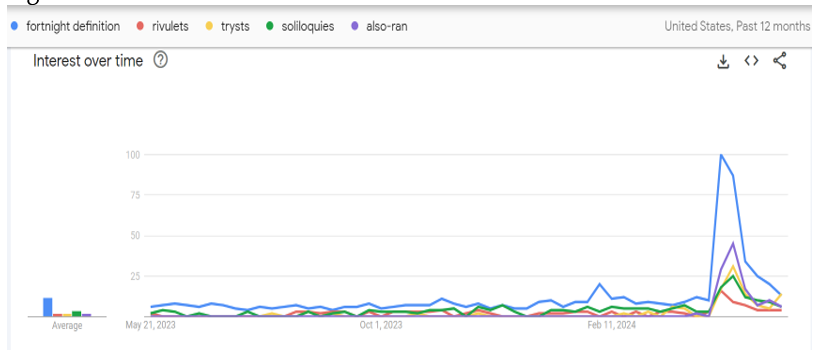

However, word choice must be approached carefully. Words can present a stumbling block to readers if the words become distracting or necessitate the use of a dictionary.[53] Sometimes Swift falls into the latter camp. For example, Google Trends shows that searches for the terms “fortnight definition,” “rivulets,” “trysts,” “soliloquies,” and “also-ran” all peaked between April 14 and April 27.[54] See Figure 1 below. Thinking that law clerks (or professors) will look up more-illustrative words with the same zeal as “Swifties” is wishful at best. Writers should elevate clarity over any strained attempt at appearing brilliant through word choice.[55]

Figure 1.[56]

- Defined Terms. Students should be mindful of specific word choices in the form of defined terms. Defining the parties, laws, or other material facts or events often streamlines the writing, and it also provides for another opportunity to interject persuasive rhetoric. In Swift’s songs, for example, she defines herself—or more so takes on the term people have placed on her—as “the albatross,” someone who brings bad luck and shame.[57] Later in the album, she labels herself as “Cassandra,” a mythological priestess blessed by the gods with the gift of prophecy but cursed so that no one believes her.[58] Using this label, Swift highlights how she spoke up about Kanye West, Kim Kardashian, and Scooter Braun, but no one believed her.[59] She also defines a former love (Matty Healy) as “the smallest man who ever lived.”[60] Through this definition, Swift constantly reminds people of how petty . . . and short . . . she thinks he is.

This same technique can be used in legal writing. Defined terms are read over and over throughout the writing, and through this repetition, they can leave a lasting impact on the reader. The most basic example can be found in criminal pleadings and briefs. Typically, the prosecution will refer to the defendant as “Defendant,” reminding the court that this individual is on trial for committing a crime. However, the defendant’s counsel will refer to the client by name to remind the court that the individual is still a person and innocent until proven guilty. Whatever the setting, students should carefully consider the lasting impact a defined term can have.[61]

- Chronology. Having spent some time reviewing arguments at the granular level, let’s zoom out to an argument’s structure. Naturally, students often recite their “Statement of the Case” in a typical, chronological fashion. But moving through a series of events is not always the most persuasive, and certainly not the most interesting, way to tell your client’s story. How Did It End? is an excellent example of telling a story from a different temporal point of view to create intrigue.[62] Instead of walking listeners through a previous relationship from the beginning, Swift draws upon the imagery of a post-mortem examination, studying the current state of the body to determine what happened in the past. By doing so, Swift invites the listener to become a detective and help piece back together the series of events that led to the couple’s demise.

In the legal context, some stories need to be told in a straightforward fashion, but students should consider whether it is more persuasive and interesting to pick their writing up at, for example, the climax of the drama or the result of the conflict. Beyond reader engagement, “[a]n anachrony can draw attention to certain facts, highlighting or emphasizing them so the reader remembers them.”[63] Flashbacks and flash-forwards can also serve to incorporate other rhetoric devices, such as foreshadowing and theme.[64] Of course, students should first be concerned about the coherence of their writing, but reader engagement and narrative should be close seconds and playing with the chronology, like Swift does, is a great way to accomplish those ends

- Anticipation of Opposition. All too often students attempt to avoid opposing arguments and hide bad facts, but effective persuasive arguments anticipate and affirmatively address opposing arguments. Swift knew that amid singing about heartbreak and despair, others would point out her lavish lifestyle of sold-out shows, designer outfits, and private jets. Instead of shying away from such arguments, she addresses them head on in I Can Do It With a Broken Heart.[65] She uses the song to express that despite “her glittering prime,”[66] she suffered from a broken heart. She persevered to give the crowd “More!,”[67] even though she was internally broken down and shattered. By the end of the song, listeners find themselves sympathetic to Swift, realizing that she isn’t immune from heartbreak despite her celebrity and wealth.

By addressing the opposing narrative through this song, Swift provides students with a masterclass on addressing opposing arguments in a persuasive manner. First, students should determine when to raise the counterargument. If the argument is central to the issue, then raising it at the forefront, like Swift, may be necessary.[68] Otherwise, the counterargument is more appropriately raised later in the writing after the reader has been persuaded by other arguments.[69] Second, students should limit the “airtime” of the counterargument, focusing instead on a strong rebuttal.[70] Third, students should characterize the counterargument so that the reader perceives it in a negative light or so that it is stripped of all importance.[71] Fourth, students should begin and end on a high note, i.e., their strongest arguments.[72] By following these steps, students can address counterarguments, even with a broken heart.

-

Conclusion

Hopefully, this piece has given you a greater appreciation of Taylor Swift and her writing abilities. Who knows? Maybe she would maKe a better lawyer than some other celebrIties out there at the Moment. More importantly, I hope this piece spurs your creativity as a professor to bring nonlegal mediums into the classroom to introduce students to the concepts of persuasive writing. In doing so, maybe we as an academy can produce more creative writers and have a little fun in the process.

[1] Like Taylor Swift’s use of “Poets,” I elected to use the non-possessive, plural “Lawyers” in the title of this article. The absence of an apostrophe in the album’s title was the subject of debate among grammatically correct “Swifties.” Although the grammatic choice may appear to be incorrect at first blush, it is simply an adjectival noun. Instead of conveying that one or more “Tortured Poets” possess ownership over the “Department,” Swift uses the noun to describe the department itself: a department of tortured poets. The same technique is used in “Dead Poets Society,” “The Baby-Sitters Club,” “the Department of Veterans Affairs,” and “the cosmetics department.” Victor Mather, Tortured Poets’ or Poets? Taylor Swift Meets the Apostrophe Police., N.Y. Times (Apr. 19, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/07/arts/music/tortured-poets-department-apostrophe-taylor-swift.html. So, Swift’s writing lesson begins before the first beat drops.

[2] One need look no further than the infamous Super Size Me documentary, wherein filmmaker Morgan Spurlock ate exclusively McDonald’s for 30 days. He gained over 24 pounds, damaged his liver, and tarnished McDonald’s name in the process. See Genci Papraniku, The Super Size Me Controversy: Is It a McFib with a Side of Lies?, Looper (May 22, 2024), https://www.looper.com/1586984/super-size-me-controversy-explained/. Fast food may not be the healthiest dietary option, but the filmmaker took steps to cast it in the worst light possible. McDonald’s quickly pointed out that Spurlock’s ailments were more likely the result of his daily consumption of over 5,000 calories (significantly more than his daily caloric needs), and viewers eventually discovered that Spurlock had concealed his consistent alcohol intake during the experiment. See Tim Carman, How Morgan Spurlock’s ‘Super Size Me’ Recast McDonald’s, Wash. Post (May 24, 2024), https://www.washingtonpost.com/food/2024/05/24/super-size-me-mcdonalds-morgan-spurlock-effect-obituary/.

[3] This concept is far from novel. Other scholars have also found that nonlegal materials are a great way to introduce persuasive legal-writing techniques. See, e.g., Mary Ann Becker, What Is Your Favorite Book?: Using Narrative to Teach Theme Development in Persuasive Writing, 46 Gonz. L. Rev. 575, 595 (2011) (“By delving into literature and connecting it with legal analysis, students unconsciously identify the three points of view existent in narrative and are able to better understand how to write a persuasive brief. They are able to make this connection because they are relating a familiar skill from their past education with a new skill from their current education . . . .”).

[4] See Colin Starger, Constitutional Law and Rhetoric, 18 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 1347, 1353 (2016) (“Rhetoric . . . provides a systematic approach to proof and persuasion that applies across all argument fields. Logos, ethos, and pathos form the backbone of this systematic approach.” (footnote omitted)).

[5] Brian Porto, Keepers of the Flame: John Roberts, Elena Kagan, and the Rhetorical Tradition at the Supreme Court, Vt. B.J., Fall 2019, at 24. I often describe the rhetoric triangle in the context of a house (which I am sure is not an original thought): logos is the foundation, the bones, and the structure; pathos is the aesthetic, the paint, and the decorations; and ethos is the builder’s certification and the quality of the materials used.

[6] For those unfamiliar, Swift intentionally capitalizes certain letters in the song to not-so-subtly reveal the antagonist of the song. See Taylor Swift, thanK you aIMee, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[7] Id. at 01:11.

[8] Id. at 01:40.

[9] Id. at 02:19.

[10] Id. at 01:16.

[11] Id. at 01:53.

[12] See Chad Baruch, A Bit of the Ol’ Razzle-Dazzle: Tips to Improve Your Legal Writing, 33 App. Advoc. 77, 81 (2023) (explaining how quality writing builds credibility with other lawyers, clients, and judges).

[13] Brian Porto, Making It Sing: How Rhetorical Techniques Can Improve Your Writing, Vt. B.J., Summer 2014, at 36, 37.

[14] See Victoria S. Salzmann, Honey, You’re No June Cleaver: The Power of “Dropping Pop” to Persuade, 62 Me. L. Rev. 241, 248 (2010) (“Writing techniques that grab readers’ attention and keep them engaged are more likely to convey the author’s point. Scholars call this the ‘decorative function’ of the literary device and acknowledge that presence alone is often enough to persuade.”); see also Porto, supra note 14, at 36 (“The late Professor Fred Rodell of Yale Law School once observed of legal writing, ‘I am the last one to suppose that a piece about the law could be made to read like a juicy sex novel or a detective story, but I cannot see why it has to resemble a cross between a nineteenth century sermon and a treatise on higher mathematics.’”).

[15] In other words, literary devices tie the writer’s foreign facts and legal arguments to ideas, concepts, and themes more familiar to the reader, which provide the advocate a persuasive “foot in the door.” See Kathryn M. Stanchi, The Science of Persuasion: An Initial Exploration, 2006 Mich. St. L. Rev. 411, 418 (2006) (“Empirical research on human behavior and decisionmaking provides some evidence that argument chains are more likely to persuade readers if the first links of the chain are well-settled or widely accepted premises.”); see also Bret Rappaport, Tapping the Human Adaptive Origins of Storytelling by Requiring Legal Writing Students to Read a Novel in Order to Appreciate How Character, Setting, Plot, Theme, and Tone (CSPTT) Are as Important as IRAC, 25 T.M. Cooley L. Rev. 267, 268 (2008) (“To be persuasive, what a lawyer writes or says must resonate with the reader and the listener. Therefore, lawyers must write and tell stories. Law students are training to be lawyers, and they must, consequently, learn to write and tell stories.” (footnote omitted)).

[16] Metaphor, Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/metaphor (last visited July 29, 2024).

[17] Indeed, four levels of metaphor appear in persuasive legal discourse: (1) those that describe legal doctrines (e.g., fruit of the poisonous tree); (2) those that articulate legal methods (e.g., the idea of “balancing” factors in an analysis); (3) those that convey a theme in the writing or a specific argument (e.g., fishing expedition, parade of horribles, wolf in sheep’s clothing, etc.); and (4) those that identify inherent views of humanity (e.g., “up” generally describes being awake or healthy while “down” generally describes being asleep or sick). See Michael Smith, Levels of Metaphor in Persuasive Legal Writing, 58 Mercer L. Rev. 919, 921-22, 928-29, 932, 941, 942-43 (2007).

[18] See Salzmann, supra note 15, at 253 (noting that “[s]ometimes the sheer complexity of a concept makes metaphor an almost indispensable aid to comprehension” (internal quotation marks omitted)).

[19] Taylor Swift, imgonnagetyouback, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 01:27 (Republic Records 2024).

[20] Taylor Swift, The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 01:16 (Republic Records 2024).

[21] Taylor Swift, The Prophecy, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 02:30 (Republic Records 2024).

[22] Stacy Rogers Sharp, Crafting Responses to Counterarguments, 10 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric: JALWD 201, 212-13 (2013).

[23] Taylor Swift, The Tortured Poets Department, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 01:36 (Republic Records 2024) (emphasis added).

[24] Taylor Swift, Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:45 (Republic Records 2024) (emphasis added).

[25] Taylor Swift, I Can Fix Him (No Really I Can), on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:05 (Republic Records 2024) (emphasis added).

[26] Taylor Swift, The Alchemy, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:11 (Republic Records 2024) (emphasis added).

[27] Gertrude Block, Language for Lawyers, Fed. Law., May 2002, at 57.

[28] A great example is Ironic by Alanis Morissette, wherein she describes numerous scenarios that are tragic but not inherently ironic. Alanis Morissette, Ironic, on Jagged Little Pill, at 00:38 (Warner Bros. 1996) (“It’s like rain on your wedding day / It’s a free ride when you’ve already paid”). Indeed, when Morissette updated the lyrics at a live recording 20 years later, she humorously and accurately observed that irony is “It’s singing ‘Ironic’ / When there are no ironies.” Robinson Meyer, Alanis Morissette Recognizes It’s Not Ironic, Atlantic (May 9, 2016).

[29] Taylor Swift, My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:28 (Republic Records 2024).

[30] The Art of Legal Satire: How Lawyers Use Wit and Irony, Legal Pro. Blog, https://legalprofessionblog.com/the-art-of-legal-satire-how-lawyers-use-wit-and-irony/#:~:text=Irony%20is%20another%20tool%20in,entity's%20stated%20principles%20and%20actions (last visited July 15, 2024).

[31] Taylor Swift, Fortnight (feat. Post Malone), on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 03:12 (Republic Records 2024).

[32] Taylor Swift, Florida!!! (feat. Florence + The Machine), on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[33] See, e.g., Michael J. Higdon, Something Judicious This Way Comes . . . the Use of Foreshadowing as a Persuasive Device in Judicial Narrative, 44 U. Rich. L. Rev. 1213, 1218 (2010) (“[F]oreshadowing operates by subtly evoking hypotheses in the reader’s mind—hypotheses that will hopefully match the writer’s ultimate conclusion, thereby making that conclusion more persuasive.”).

[34] My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys, supra note 30.

[35] Id. at 00:16.

[36] Id. at 01:17.

[37] Id. at 02:47.

[38] Id. at 00:49.

[39] Id. at 02:38.

[40] Taylor Swift, So High School, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[41] Id. at 00:57.

[42] Id. at 01:28.

[43] Id. at 01:52.

[44] Id. at 01:59.

[45] Taylor Swift, Down Bad, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[46] Id. at 01:27.

[47] Id. at 00:55.

[48] Id. at 01:34.

[49] Taylor Swift, Fresh Out the Slammer, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:58 (Republic Records 2024).

[50] “Poetry and lyrics [and legal writing] are very similar. Making words bounce off a page.” Taylor Swift Quotes, BrainyQuote, https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/taylor_swift_579491 (last visited July 16, 2024).

[51] Taylor Swift, Fortnight (feat. Post Malone), on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 01:03 (Republic Records 2024).

[52] The Alchemy, supra note 27, at 01:55 (“Shirts off, and your friends lift you up over their heads / Beer sticking to the floor / Cheers chanted, cause they said / There was no chance, trying to be / The greatest in the league / Where’s the trophy? / He just comes running over to me”).

[53] See Stephen E. Smith, A Rhetorical Exercise: Persuasive Word Choice, 49 U.S.F. L. Rev. F. 37, 38 (2015) (reminding that the purpose of word choice “is to persuade, not to distract”).

[54] As you can see in Figure 1, “fortnight definition” actually had a small peak in early February, when Swift began releasing her song titles. See, e.g., Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), Instagram (Feb. 5, 2024), https://www.instagram.com/p/C2_OIOtOAoM/?igsh=MXR5Znp6aW1lMGJiaQ==.

[55] The same caution applies to oral argument. University of Michigan law professor Richard Friedman stumped Supreme Court justices and slightly derailed oral argument when he described a question as “orthogonal.” Debra Cassens Weiss, Supreme Court Word of the Day: Orthogonal, ABA J. (Jan. 12, 2010), https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/supreme_court_word_of_the_day_orthogonal. For this reason, I make it a practice in my class to ask students to define more-illustrative words in their oral arguments.

[56] Google Trends, https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?geo=US&hl=en (add search terms: “fortnight definition,” “rivulets,” “trysts,” “soliloquies,” and “also-ran” and set duration for “Past 12 months”) (last visited May 22, 2024).

[57] Taylor Swift, The Albatross, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 00:31 (Republic Records 2024).

[58] Taylor Swift, Cassandra, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology, at 01:24 (Republic Records 2024).

[59] Shelby Stivale, Who Is Taylor Swift’s ‘Cassandra’ About? Lyrics Might Hide Message About Kanye West or Scooter Braun, Us Weekly Mag. (Apr. 19, 2024), https://www.usmagazine.com/entertainment/news/who-is-taylor-swifts-ttpd-song-cassandra-about-lyrics-explained/.

[60] The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived, supra note 21, at 01:08.

[61] For this reason, students must be careful not to mischaracterize the defined item and thereby undermine their credibility.

[62] Taylor Swift, How Did It End?, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[63] Jennifer Sheppard, “All We Have to Decide Is What to Do with the Time Given to Us”: Using Concepts of Narrative Time to Draft More Persuasive Legal Documents, 106 Marq. L. Rev. 831, 846 (2023).

[64] Id. at 845 (“Even those legal stories that appear linear and straightforward are often ‘filled with departures from a literal chronology’ where the storytellers bend and shape time within their stories to accommodate their purpose and the demands of the narrative.”).

[65] Taylor Swift, I Can Do It With a Broken Heart, on The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology (Republic Records 2024).

[66] Id. at 00:23.

[67] Id. at 00:57.

[68] See Sharp, supra note 23, at 203 (“The theory [of inoculation] is that introducing a ‘small dose’ of a message contrary to the persuader’s position makes the message recipient immune to attacks from the opposing side.”).

[69] See id. at 205 (noting that counterarguments are generally more effective “once the reader has been loosely persuaded by favorable information”).

[70] See id. at 218 (“Explicit rebuttal of counterarguments should be buried in the middle, where they will receive less attention and so that the writer can make both a strong first impression and conclude with its best, offensive points.”).

[71] Id. at 206-07.

[72] See id. at 217-18 (also noting that advocates should consider ending with the weakest counterargument to appear stronger).