The Second Draft - Volume 37, No. 1

“What page limit should I aim for?” Or why I don’t give page limits, and what I do instead DOWNLOAD PDF

October 31, 2024I hate page limits. I also hate overlong legal writing, but I don’t think page limits are the best solution for that problem. Overlong legal writing happens for three main reasons: wordiness, writing about irrelevant issues, and providing too much rule explanation or rule application on relevant issues. Much has been written on the first of these,[1] and we all work with our students on avoiding the second by teaching them how to identify relevant issues. In this essay, I’ll focus on the third: I’ll quickly explain why I hate page limits and then describe the various length-related strategies I’ve tried to teach students over the years. Finally, I’ll explain how I’m using my latest, and I think best, lesson: identifying a ballpark number of paragraphs to spend on each issue.

-

Why I don’t assign page limits

I think I’m rare among legal writing faculty in that I usually don’t give my students page limits. I have a few reasons for this decision. The first is that I was scarred by an experience during my first year of teaching, at Vermont Law School.[2] The then-director of legal writing required the students to follow the United States Supreme Court rules. Unfortunately, the page limit for briefs was FIFTY PAGES, and far too many of my students thought that a 50-page limit meant they had to write a very long paper. On a one-issue Fourth Amendment case, I routinely received 35-page briefs, full of repetition. I remember one night when, exhausted from paper grading, I checked the back page of the next brief I took from the pile: it was actually 50 pages long! I nearly wept. And I think many students still have this attitude about page limits. The title of this essay quotes a student who I taught in the fall of 2022. As the quote suggests, for too many students, the page limit becomes a page goal.

Another reason I don’t give page limits is that I don’t think in pages, so it’s hard for me to give an estimate. And there’s educational value in not giving our students a page limit to shoot for. In practice, a client is not going to say, “I hope you can help me. I have a 15-page legal problem, and I don’t know where to go.” Most court page limits are generous enough to allow non-wordy writing that can fully address even somewhat complex issues. Our students need to get some experience in figuring out the length issue for themselves.

Finally, I agree with the adage that you don’t learn anything about a student’s sentence-level writing on page twenty that you didn’t already know on page ten. But, I do think I can learn things about a student’s thinking and research skills on page twenty. And yes, that means that sometimes I get papers that are too long. Those are teachable moments–we talk about why it’s too long and how to avoid that problem the next time. And my students know that I limit the pages I do sentence-level critiquing on; it’s their job to apply my sentence-level guidance on all sentences as needed. After I reach my sentence-level limit, I read only for new problems in research, large-scale organization, and substance.

-

Techniques I’ve used to help students determine appropriate length

All this is not to say, though, that I enjoy overlong papers or that I refuse to give guidance to my students. I love to use formulas (heuristics, more precisely) in legal writing.[3] I don’t want to tell students exactly what to do, but I’m glad to give them a set of questions they can use to help make decisions. To analyze a legal issue, for example, writers usually need to answer three crucial questions: 1. What rule governs this issue? 2. What does this rule mean? 3. How does that rule apply here? Legal writing fans will recognize the core elements of the CREAC formula.[4]

To help my students answer the “how long should this be?” question, I’ve tried a few methods over the years. For starters, I tell them that they should look at how abstract or concrete their phrases-that-pay[5] are. The more abstract the language of the phrase-that-pays, the more likely it is that they will need a longer rule explanation, rule application, or both. Likewise, if both sides have strong arguments on an issue, students will need to use more length to address those arguments.

I have illustrated this guidance with a graphic of an abstract-concrete axis crossing a controversial-not controversial axis. Thus, if the language of the phrase-that-pays is abstract, and the relevant issue is controversial, they can expect a longer CREAC for that issue. If the phrase-that-pays is concrete, and its application is not controversial, they may not need to address it all, or merely to “raise and dismiss” it, as my friend Alison Julien tells her students at Marquette.

This guidance worked for many students, but some students still belabored obvious points or simply got lost when trying to answer the “how long” question. I now recommend that for each governing rule, students should identify each possible phrase-that-pays, and then answer a series of questions to determine which of four categories to put the issue in: Ignore, Tell, Clarify, or Prove.[6]

I’ve written about these categories in textbooks, so I won’t belabor them here, but as a quick example: In a DUI case, the phrases-that-pay in the relevant statute would presumably be that the prosecution must establish that a person (first possible issue) operated (second possible issue) a vehicle (third possible issue) while under the influence of a controlled substance (fourth possible issue). In most cases, “person” and “vehicle” would be ignore issues. You wouldn’t spend even a sentence saying, “as a homo sapiens, Ms. Driver is covered by the language imposing requirements on ‘persons.’” Likewise, you wouldn’t spend a sentence saying “a Ford Fusion is a ‘vehicle’ under the statute.” On the other hand, suppose the defendant was arrested while driving a motorized barstool? (That happened in Ohio a few years ago.) If this issue had never been litigated, it might be a prove issue. But if your state courts had already ruled that motorized barstools meet the definition of “vehicle,” then you would merely tell the reader, “Motorized barstools are ‘vehicles’ under § 123.123 of the Vanita Revised Code. See Vanita v. Idiot, 101 R.E.2d 222, 255 (Van. 2009).”[7]

Clarify issues are issues that are not controversial, but that require a bit of legal or factual detail to clarify the lack of controversy. For example, if the facts seem to indicate that a party might be able to recover under a whistleblower statute, a memo writer might need to take a paragraph to clarify that the statute’s specific requirements do not cover the party in that case. I tell students to think of a clarify analysis as a “CRAC” unit of discourse. The writer must articulate the conclusion for that issue, articulate the rule, apply the rule to the facts, and articulate an appropriate connection-conclusion. No rule explanation is needed. Prove issues are the last category, and as you’ve probably already guessed, that’s the category reserved for controversial issues that need a full CREAC analysis.[8]

Students find the ignore-tell-clarify-prove categories helpful. Frequently, as I describe in more detail below, we’ll discuss in conferences whether they’ve hit all of the needed tell issues, or whether an issue is a clarify or a prove.[9]

-

Using paragraphs as a meaningful measurement

But still they seek guidance on length. In the Fall of 2022, I finally realized that by the time students were in the final stages of drafting their memos or briefs, they had the information needed to use a more sophisticated method to figure out how long their documents should be. Rather than ask how many pages to devote to each issue, however, they should ask about paragraphs.

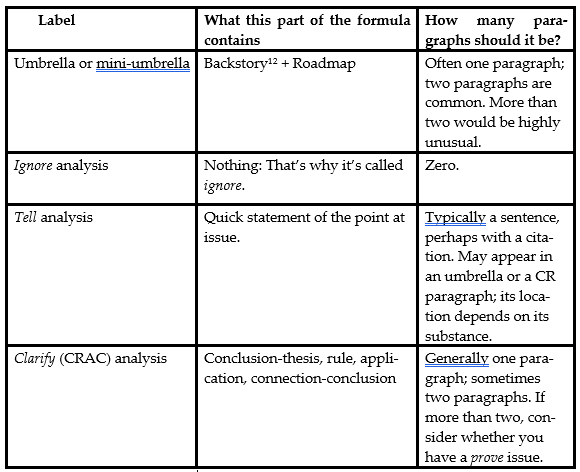

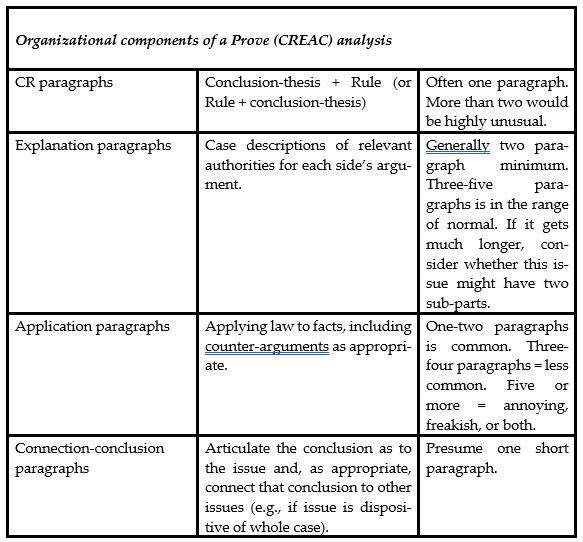

As part of the writing process, memo and brief writers must determine how many issues they will address, and how they will organize those issues. They must identify how many prove/ CREAC issues they have, how many tell issues (often handled in introductory material), and how many clarify/CRAC issues. Then they must identify how they will organize the needed units of discourse: For example, do they have two or more prove issues that are sub-issues of a major point? How many umbrellas[10] and mini-umbrellas will they need? With these Lego bricks of structure in mind, students can determine a paragraph-based length estimate, as shown in the following table:[11]

Let’s say a student was writing a memo on a DUI charge under the statute described earlier. The defendant was found behind the wheel of a stopped car on the side of the road. It was a push-button car (rather than a key-start), and he had the key fob in his pocket. The defendant’s counsel is arguing that the intoxication test was invalid and that even if it was valid, the defendant wasn’t “operating” the vehicle. In that jurisdiction, a person is “operating” if they are behind the wheel of a parked car with the key in the ignition; the state courts hadn’t addressed a key fob case yet. Thus, the writer would need one umbrella to lay out the rule and the roadmap. There would be two ignore issues: “person” and “vehicle.” And there would be two prove issues: “intoxication” and “operating.” The umbrella could probably be one paragraph. The “intoxication” issue turns out to have several arguments relevant to each side. The writer estimates one CR paragraph, four explanation paragraphs (addressing six cases), two rule application paragraphs, and one connection-conclusion paragraph. The total estimate for that issue is eight paragraphs.

The operating issue has fewer relevant cases. The writer estimates one CR paragraph, three explanation paragraphs (addressing four cases), one application paragraph, and one connection-conclusion paragraph. The total for that issue would be six paragraphs. The total estimate for the whole analysis would be fifteen paragraphs. This total does not translate into pages, because some of the paragraphs could be quite short, but a rough guess would be five to seven pages. And of course, this estimate doesn’t count other required elements like a statement of facts and the like.

-

Heading off possible problems

As soon as I mention using paragraphs for measurement, I can imagine some of you rolling your eyes, thinking of the giant paragraphs that some students produce. As with many formulas, this formula doesn’t do all the work: it just helps guide decisions.

Many of our students have been taught in high school that each paragraph “develops one idea.” That rule sometimes leads to paragraphs so huge they could win a ribbon at a county fair (“I grew it from when it was just a sentence fragment!”). I use two methods to limit paragraph length. The first method is a simple mandate: I require at least two paragraph breaks per page on double-spaced documents. Yes, that’s a mechanical rule, but it’s based on realities about reader needs and reader behavior.

The second method is one that many legal writing faculty use: I think of the elements of legal writing separately, and I provide substantive guidance on what information each element needs, as indicated in the table above. For example, in the classic CREAC formula, the “CR” part usually goes together. We discuss articulating a conclusion-thesis[13] and deciding whether it should appear before or after the rule, whether the writer must move from a general rule to a more narrow rule, and whether this issue has any tell issues that must be addressed right away. Even if the writer must answer yes to all of these questions, they would rarely need to spend more than two paragraphs here. More often, one paragraph would be plenty.

The rule explanation typically consists of two or more paragraphs of case descriptions, whether textual or parenthetical. I have developed a formula for what the reader should be able to glean from an effective case description: the relevant issue (always), how the court disposed of that issue (always), the relevant facts (almost always), and the relevant reasoning (it depends).[14] When determining how many case descriptions to include, we talk about the concepts noted above: How abstract is the language of the phrase-that-pays? How many arguments could each side make? Does this phrase-that-pays have different facets, so that talking about more cases (or devoting more than one paragraph to one case) will help the reader’s understanding?

I can then work with students on how to streamline their writing to achieve their targeted length for each CREAC component by avoiding wordiness, using topic sentences effectively with case descriptions,[15] and the like. For example, many textual case descriptions can be only two sentences long, and they should rarely be more than a paragraph. A parenthetical case description should generally use no more than three lines (if it does, perhaps let it breathe free and make it a textual case description). By deciding how many textual and parenthetical case descriptions they need, students can estimate how many paragraphs they will need for each issue.

I won’t give my guidance for rule application, connection-conclusions, or umbrellas here, but the preceding table gives you the idea.[16] The key to figuring out length is to focus on elements for each CREAC and other components of legal writing. Students should estimate how many paragraphs each element will need, and add them up to identify how many paragraphs they may need for the Discussion or Argument section.

Of course, this idea doesn’t make the length decision easy, but I hope it makes the decision easi-er. And it also helps me diagnose concerns and focus student attention in one-on-one conferences. If a draft is too long, where is the problem? Is it a problem in how they are choosing to discuss their issues? For example, is the writer using a prove analysis where a tell or clarify description would be more appropriate? Is the writer taking time clarifying something that any reasonable reader would accept without extended discussion (clarifying instead of telling), or making a point that to an experienced reader would go without saying (telling instead of ignoring)? Within the explanation part of prove analyses, are they talking about cases that illustrate a facet of the rule that is not at issue? Then, we can move to how students can streamline their writing on a sentence- or word-level. Are their case descriptions too wordy?[17] Are they spending time on irrelevant facts or analogies in their rule explanation? And so on.

Writers should always ask themselves questions like these, whether the length constraints come from a court-imposed or professor-imposed page limit, and even if they have no mandated length constraints. A brief or memo should be only as long as it needs to be. My goal with this method is to empower students to make the length decision themselves.

[1] E.g., Anne M. Enquist, Laurel Currie Oates, & Jeremy Francis, Just Writing: Grammar, Punctuation, and Style for the Legal Writer (6th ed. 2022); Joseph M. Williams & Joseph Bizup, Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace (13th ed. 2020); Richard Wydick & Amy Sloan, Plain English for Lawyers (6th ed. 2019).

[2] Shockingly, it was Fall Semester of 1983.

[3] For a discussion of how and why I use formulas and why I think they don’t lead to cookie-cutter writing, see Mary Beth Beazley, How Formulas Help Legal Writers and Legal Readers, YouTube (Nov. 2, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6k3Ugk4zO7M&t=28. (Searching “Beazley formulas” on YouTube will get you there.)

[4] See, e.g., Mary Beth Beazley, Fire, Flood, Famine & IRAC?, 10 Second Draft 1, 2 (Fall 1995) (arguing in favor of using IRAC, and adding an explanation to the rule part of the acronym).

[5] I use the term “phrase-that-pays” where most of my colleagues would use “key terms.” I think “phrase-that-pays” is more memorable and more fun. See, e.g., Mary Beth Beazley, A Practical Guide to Appellate Advocacy 72 (6th ed. 2022) (explaining benefits of identifying phrases-that-pay in legal rules).

[6] Mary Beth Beazley & Monte Smith, Legal Writing for Legal Readers: Predictive writing for first-year law students 110-15 (3d ed. 2022) (explaining how to decide level of depth using continuum and/or flowchart).

[7] “Vanita” is a made-up state name. I learned early in my career to stop setting research problems in fictional jurisdictions, but I often use the fictitious jurisdiction of “Vanita” in examples. “R.E.2d” is also fictional; it stands for “Regional East, Second Series.”

[8] See also Richard K. Neumann, Jr. & Kristen Konrad Tiscione, Legal Reasoning and Legal Writing ch. 12 (7th ed. 2013) (using prove in much the same way that CREAC uses explanation).

[9] As a side benefit, I use these terms when I advise students on exam writing. In particular, I warn them to include all possible issues with at least a tell analysis. If the professor doesn’t care about the issue, a one-sentence tell won’t cost much time. But if the issue is a significant one, the student may at least get partial credit. Further, by writing out the tell analysis, students may realize the issue needs more attention.

[10] I believe Linda Edwards first coined this label for the paragraph or paragraphs that introduce issues and/or set readers up for sub-issues. E.g., Linda H. Edwards & Samantha A. Moppett, Legal Writing: Process, Analysis, & Organization (8th ed. 2022).

[11] I developed this chart when writing this essay, which I plan to share with my students as they begin working on their briefs. I also hope to incorporate it (or a revised draft) in a textbook revision.

[12] See, e.g., Beazley, supra note 5, at 246-50 (explaining legal backstory).

[13]E.g., Beazley & Smith, supra note 6, at 138.

[14]See Beazley, supra note 5, at 120-22; Mary Beth Beazley & Monte Smith, Briefs and Beyond: Persuasive Legal Writing 142-45 (2021); Beazley & Smith, supra note 6, at 152-62.

[15] See, e.g., Beazley & Smith, supra note 14, at 226-31; Beazley, supra note 5, at 240-45.

[16] See Beazley & Smith, supra note 6, at 136-45, 213-25; Beazley & Smith, supra note 14, at 24-31, 215-23; Beazley, supra note 5, at 89-108; 246-53.

[17] For guidance on how to write succinct case descriptions, see Beazley, supra note 5, at 123-25; Beazley & Smith, supra note 14, at 149-50; Beazley & Smith, supra note 6, at 162-67.